The Strategic Value of Plant Varieties: Whoever Innovates, Wins

25 Jul 2025 | Newsletter

A new chapter is unfolding in the field of agricultural innovation in Brazil. In April 2025, the Senate’s Committee on Agriculture and Agrarian Reform unanimously approved Senate Bill No. 404/2018, which proposes significant amendments to the Brazilian Plant Variety Protection Law (Law No. 9,456/1997). Although the bill must still undergo a supplementary round of voting, it has already generated considerable anticipation in the agricultural sector. The key proposal is to extend the term of protection for plant varieties: from 15 to 20 years in general, and from 18 to 25 years for grapevines, fruit trees, forest species, ornamental plants, and sugarcane.

This legislative update aligns Brazil with the 1991 Act of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, which established the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), the major international framework governing the subject. Member countries of the Convention have already adopted similar protection periods, thereby ensuring legal certainty and predictability for plant breeders (“Breeders”). The objective is clear: to incentivize the development of new plant varieties by ensuring a return on investment for those dedicating time and resources to this critical work.

The next step is a supplementary round in the Senate. At this stage, amendments may be proposed, but a new integral substitute is not allowed. If approved, the bill will proceed to the Lower House of Representatives. It is anticipated that, once enacted, the new provisions will apply both to new and pending Plant Variety Protection applications before the Brazilian PVP Office (SNPC), under the authority of the Ministry of Agriculture.

What Is a Plant Variety and Why Is Its Protection Important?

In Brazil, “cultivar” is the legal term designating a plant variety developed through plant breeding. It must be stable, uniform, and clearly distinct from existing varieties. Legal protection is granted through a certificate issued by the SNPC, following rigorous technical evaluation.

PVP confers upon the Breeder the exclusive right to commercially exploit the plant variety for the duration of its term of protection. This fosters investment in research, enhances competitiveness, and promotes solutions tailored to national agricultural conditions.

Beyond economic impact, PVP is crucial for scientific advancement. It provides both public and private sector Breeders with a mechanism to ensure that their efforts result not only in technical progress but also in financial and institutional recognition. From a commercial standpoint, PVP strengthens Brazil’s position in international markets. Protected varieties meet quality standards and offer assurance of reliability and performance to buyers.

On April 25, 1997, Law No. 9,456 was enacted, establishing the rights to Plant Variety Protection in Brazil. On June 30, 1999, Brazil acceded to the 1978 Act of the UPOV Convention via Decree No. 3,109. The Industrial Property Law (Law No. 9,279), which governs patent rights, was enacted on May 14, 1996. Prior to these legislative milestones, new plant varieties, essentially derived varieties (EDV’s), DNA sequences, genetic events/traits, and related innovations were not covered by Intellectual Property rights. It is important to note that plant variety protection and patent protection are complementary legal mechanisms, each addressing different categories of innovation.

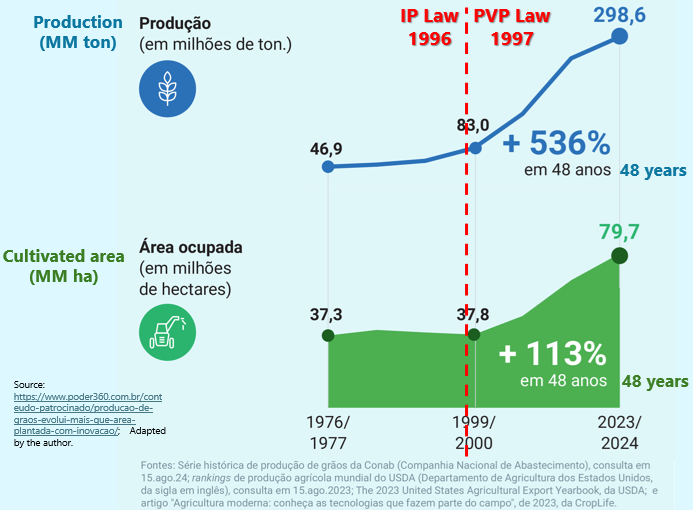

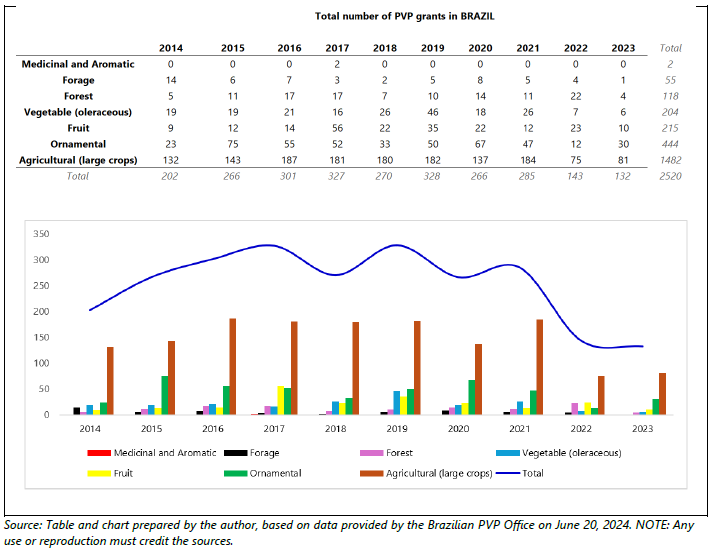

Between 1976 and 2024, grain production increased by 536%, while cultivated land area expanded by 113%. This rise in productivity is largely attributed to innovations in agribusiness. Notably, the enactment of the PVP Law and the Patent Law in 1996 and 1997 marked a turning point, coinciding with the end of two decades of stagnation and the onset of two decades of sustained growth:

Plant Varieties That Drive Excellence

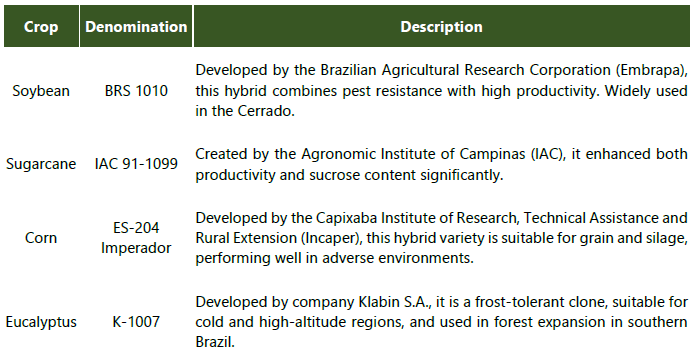

Below are examples that demonstrate how PVP fosters agricultural advancement:

These varieties are the result of years of research, field trials, and investments by both public and private entities.

In April 2025, Blue Origin’s NS-31 space mission transported plant varieties of sweet potato (“Beauregard,” by Embrapa and Louisiana State University; and “Covington,” by North Carolina State University) and chickpea (“BRS Aleppo,” by Embrapa) into space. This initiative is part of the Space Farming Brazil Network – a partnership among Embrapa, the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB), and 22 research institutions (including IAC, Esalq, USP, Ufscar, UFV, and ITA) – aimed at studying how these plants grow in low-gravity, high-radiation environments. The goal is to identify plant varieties that are more resilient, nutritious, and adaptable to extreme conditions, with agronomic characteristics suited for cultivation in space missions.

The selected species offer substantial advantages for space agriculture: they are resilient, easy to manage, and nutritionally valuable. For instance, sweet potatoes provide low glycemic carbohydrates, protein potential, and antioxidant bioactive compounds that mitigate radiation effects – beneficial for astronauts. Chickpeas, in turn, are notable for their high protein content. This research not only contributes to sustaining space missions but also addresses terrestrial agricultural challenges, such as water and nutrient scarcity, and may accelerate innovation in plant breeding to combat climate change.

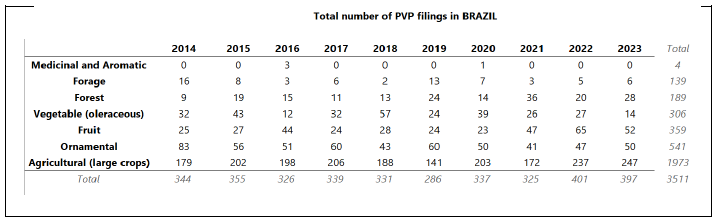

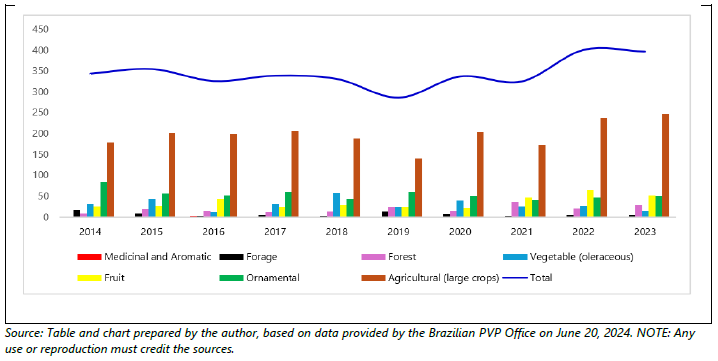

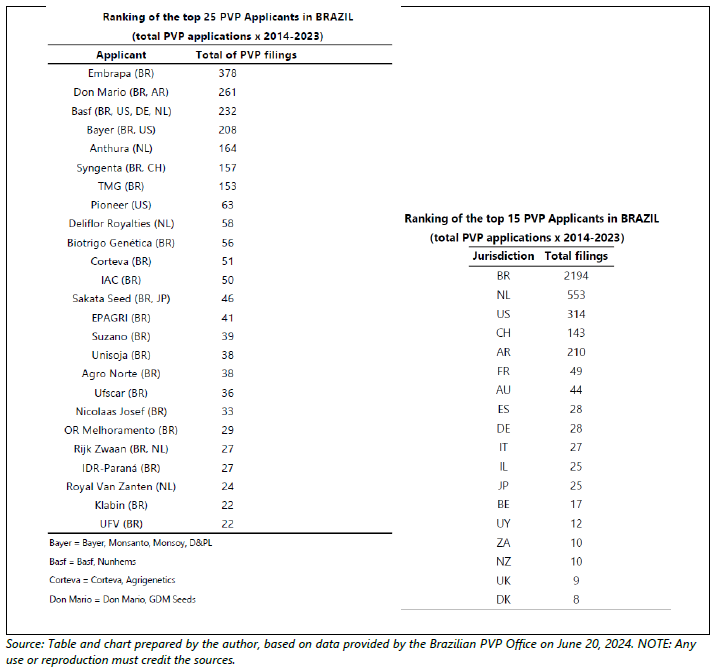

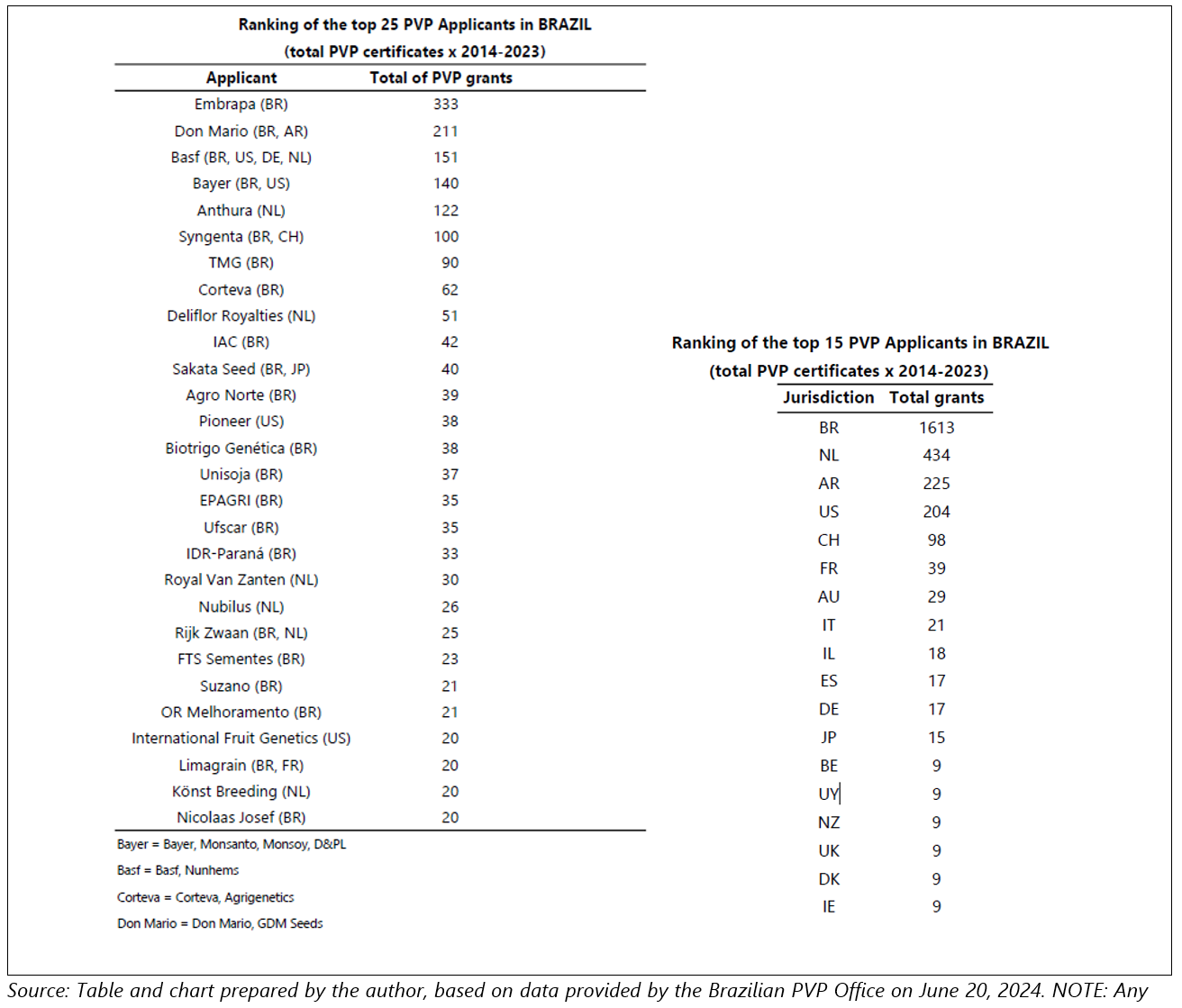

The Evolution of Plant Variety Protection

Final Considerations

Protecting plant varieties is not merely about recognizing a right – it is a strategic measure to ensure that Brazil remains at the forefront of global agriculture. By modernizing its legal framework, the country reaffirms its commitment to responsible innovation and to valuing scientific efforts in the field.

Senate Bill No. 404/2018 is not only a corrective to outdated legislation but also a forward-looking initiative that positions Brazil for a future in which the knowledge generated by its plant breeders is duly rewarded and translated into tangible benefits for society. Without innovation in plant varieties, agriculture will not be equipped to meet tomorrow’s challenges.