Use of Andy Warhol’s “Orange Prince” on Vanity Fair Cover Infringes Underlying Photograph; Supreme Court Rejects Fair Use Defense

11 Aug 2023 | Newsletter

In a case closely watched by artists and copyright practitioners, the U.S. Supreme Court struck a blow to the copyright fair use defense in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 143 S.Ct. 1258 (2023), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-869_87ad.pdf. The Court ruled that Andy Warhol Foundation’s licensing of Warhol’s “Orange Prince” for use on a magazine cover did not qualify as fair use.

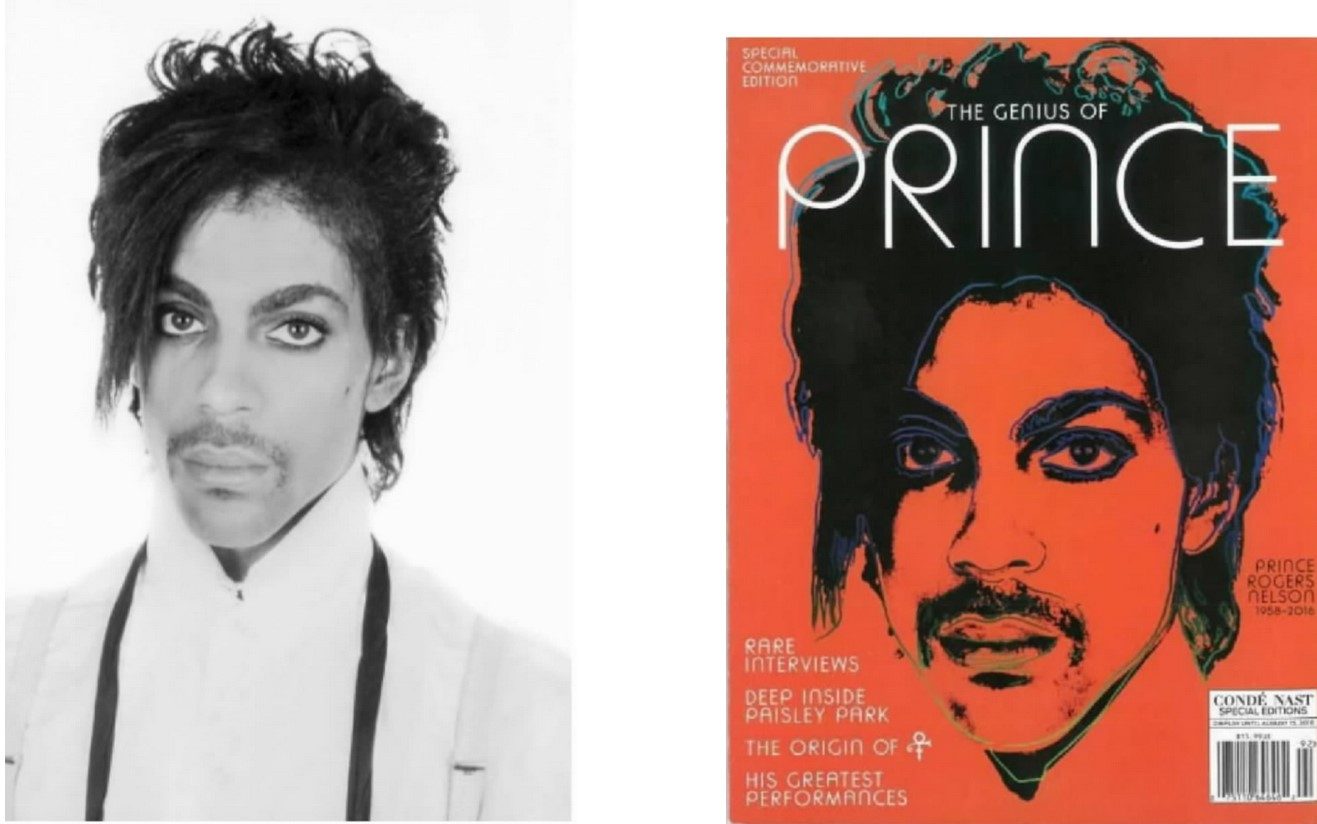

Lynn Goldsmith, a professional photographer, was commissioned by Newsweek in 1981 to photograph Prince, then an “up and coming” musician. Goldsmith retained the copyright in her photographs and subsequently granted a limited license to Vanity Fair for a “one time” use of her photo as an “artist reference.” Vanity Fair hired the well-known artist Andy Warhol to create a silkscreen based on Goldsmith’s photo for the November 1984 issue of Vanity Fair. It credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph” and paid her $400.

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol had made a total of 16 different works based on Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince, collectively known as the “Prince Series.” In 2016, following Prince’s death, Vanity Fair obtained a license from Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (“AWF”) to use another of the works (“Orange Prince”) for the cover of a special edition commemorating Prince. AWF received $10,000 and Goldsmith received nothing.

Goldsmith’s photograph and the Vanity Fair cover featuring “Orange Prince” are shown below:

After Goldsmith informed AWF that she believed its use was infringing, AWF filed an action for declaratory judgment of non-infringement or fair use. Goldsmith counterclaimed for copyright infringement. The district court found fair use and ruled in favor of AWF. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and held that the challenged use infringed Goldsmith’s copyright. It considered the four fair use factors enumerated in the Copyright Act and held that all of them favored Goldsmith. The Second Circuit determined that the first factor – “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes” – weighed against fair use because the use at issue was not transformative. It explained that the “transformative purpose and character must, at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another’s artistic style on the primary work.”

The Supreme Court affirmed the Second Circuit’s decision. It explained that the first fair use factor “focuses on whether allegedly infringing use has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism.”

If an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some justification for copying.

In this case, Goldsmith’s photograph and AWF’s use of it “share substantially the same purpose,” and moreover, AWF’s use was of a commercial nature. The Court noted many other publications showed photographs of Prince on the cover of commemorative editions. Thus, even though Orange Prince “added new expression to Goldsmith’s photograph,” AWF’s licensing of this work to Vanity Fair was an infringement.

The Court recognized that one of the exclusive rights of a copyright owner is the right to make derivative works, such as a movie adaptation of a book; and the definition of derivative work includes “any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.” An overbroad application of transformative use, however, would interfere with the copyright owner’s derivative work right.

The Court noted that it is common for photographers to license their photographs for use in magazines or to create derivatives, and such licenses “are how photographs like Goldsmith make a living.” Thus, they provide “an economic incentive to create original works, which is the goal of copyright.”

The Court emphasized that fair use (and the first factor in particular) requires an analysis of the specific “use” that is alleged to be an infringement: “The same copying may be fair when used for one purpose but not another.” Thus, the Court’s rejection of AWF’s fair use defense was limited to AWF’s commercial licensing of Orange Prince for the Vanity Fair cover – the alleged infringement in this case – and “the Court expresses no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of any of the original Prince Series works.” For example, the Court noted that if AWF’s use had been for teaching purposes, it would change the analysis.

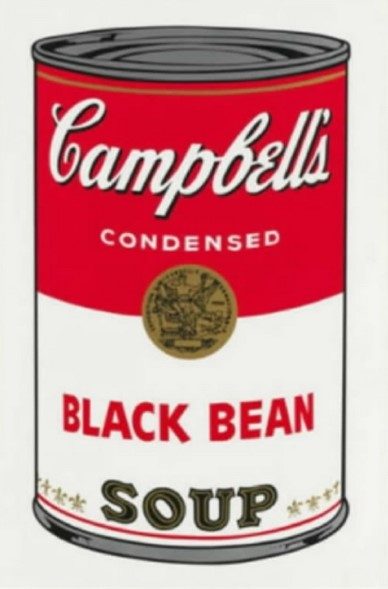

Indeed, the Court recognized that “derivative works borrowing heavily from an original” can, under some circumstances, qualify as fair use. The Court cited as an example Warhol’s own Soup Can series, such as the work shown below, which replicates Campbell’s copyrighted advertising logo:

The Court distinguished this work from the use at issue in the present case:

The purpose of Campbell’s logo is to advertise soup. Warhol’s canvases do not share that purpose. Rather, the Soup Cans series uses Campbell’s copyrighted work for an artistic commentary on consumerism, a purpose that is orthogonal to advertising soup. The use therefore does not supersede the objects of the advertising logo.

The situation might be different, the Court explained, if Warhol licensed his Soup Cans series to a soup business to serve as its logo. Moreover, the Court noted, Warhol’s Soup Cans series targeted the Campbell’s logo – “a symbol of an everyday item for mass consumption” – as the object of its commentary. Orange Prince, by contrast, did not provide any commentary on Goldsmith’s photographs.

The Court also rejected AWF’s argument that its use was transformative because Warhol’s Prince Series provided a new meaning and message to Goldsmith’s photograph (for example, as the district court noted, it portrayed Prince as “an iconic, larger-than-life figure”). Echoing the Second Circuit, the Court explained that the first fair use factor cannot weigh in favor of “any use that adds some new expression, meaning or message.” Otherwise, the Court explained, “transformative use” would “swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works.” Again, the Court focused on AWF’s specific licensing of Orange Prince for the magazine cover – a use that could have been accomplished by Goldsmith’s original photo.

Justice Kagan wrote an impassioned dissent in favor of AWF’s fair use defense, praising Warhol’s art and predicting that the majority’s opinion “will stifle creativity of every sort,” “thwart the expression of new ideas,” and “make our world poorer.” However, the majority responded that its decision was a “continuation” of existing copyright law and would, in fact, help to promote creativity by rewarding artists (such as Goldsmith) for their original works.

It will not impoverish our world to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work. … [P]ayments like these are incentives for artists to create original works in the first place. Nor will the Court’s decision, which is consistent with longstanding principles of fair use, snuff out the light of Western civilization, returning us to the Dark Ages of a world without Titian, Shakespeare, or Richard Rodgers.

Time will tell the impact of the Court’s decision and whether Justice Kagan’s fears will come to pass.